Portland’s Housing Affordability Challenge

Mayor Charlie Hales recently made headlines with a proposal that the city allow small houses to be built on government owned land in an effort to increase affordable housing options. Hales’ outside-the-box idea reflects a couple of realities. The first is that housing affordability continues to erode in Portland. The second is that the city’s current set of tools to promote and develop affordable housing is not sufficient to meet growing demands.

The challenge of housing affordability is not specific to Portland, of course. All one needs to do is to look to our neighbors to the north in Seattle and our neighbors to the south in San Francisco to see that the cost of housing in cities on the west coast, and many large cities throughout the US, is on the rise. This is especially true in neighborhoods that are close to the downtown core like many of the neighborhoods in the SE Uplift coalition area.

The challenge of housing affordability is not specific to Portland, of course. All one needs to do is to look to our neighbors to the north in Seattle and our neighbors to the south in San Francisco to see that the cost of housing in cities on the west coast, and many large cities throughout the US, is on the rise. This is especially true in neighborhoods that are close to the downtown core like many of the neighborhoods in the SE Uplift coalition area.

Portland’s inner city neighborhoods are becoming less accessible to people from all income levels. Many fear that if we continue down the current path, the neighborhoods we live in will soon be exclusively the province of the wealthy. This loss of income diversity hurts everyone (see last month’s newsletter article Do Renters Matter?).

So what can be done about it? The reality is that in a society in which market forces drive housing prices, there isn’t a magic bullet solution to assure that people at the lower end of the income spectrum can afford to live everywhere in the city. We know from experience that the market alone won’t provide affordable housing in all areas. We also know that it will take citizen advocacy and strong political leadership for the city to enact new policies aimed at maintaining and increasing affordable housing.

With this article we take a look at what programs and policies Portland (and its varied partners) currently has to address affordable housing needs. Then we look at some approaches other cities across the country are taking.

Portland’s Affordable Housing Programs and Policies

- Direct Financial Assistance for Rental Housing Development: The Portland Housing Bureau (PHB) encourages the construction of affordable multi-family rental housing by offering non-profit and for-profit developers access to low-interest and favorable-term loans. The city also administers grants programs that use federal and local funds to develop, rehabilitate, and preserve affordable housing. In June, PHB announced that there was $17,500,000 available in funds for 2014.

.. - Tax Increment Financing (TIF): As part of the city’s urban renewal districts, money (a minimum of 30% of government spending) is set aside to provide affordable housing within the districts. In 2012-13, about $28 million in TIF funding was spent to develop units in urban renewal districts such as Interstate, Gateway, and Lents. TIF funding was also used to help finance the Bud Clark Commons in Old Town, a housing facility that aims to help people transition out of homelessness.

- Limited Tax Exemption: Portland offers three different limited tax exemption programs. The first, Homebuyer Opportunity Limited Tax Exemption (HOLTE), is designed to promote affordable single family homes. Under HOLTE, new single-unit homes can receive a ten-year property tax exemption on structural improvements to the home as long as the property and owner meet certain income requirements. This provides some tax relief to those who may not otherwise be able to afford owning a home. In 2012-13, there were 1,835 units that received HOLTE status.

The second program is the Multiple-Unit Limited Tax Exemption (MULTE), which offers a similar ten-year tax break to owners of buildings such as apartments that meet certain affordable housing thresholds. In 2012-13, there were 663 units qualified for MULTE.

The third program is the Non-Profit Low Income Limited Tax Exemption (NPTLE), which provides a property tax exemption for low-income housing owned by nonprofit organizations. In 2012-13, there were 9,579 units that received NPLTE exemptions.

Public Housing: Portland is not engaged in constructing the type of large-scale publicly owned housing projects that sprung up across the United States after World War, but instead there are projects such as Gray’s Landing, an affordable housing building for veterans at risk of homelessness and low-income families. PHB invested in the building’s development in the South Waterfront (using TIF), partnering with REACH CDC, which now owns the building. The major limiting factor for city-developed housing is the lack of funds allocated for purchasing land and for development.

Public Housing: Portland is not engaged in constructing the type of large-scale publicly owned housing projects that sprung up across the United States after World War, but instead there are projects such as Gray’s Landing, an affordable housing building for veterans at risk of homelessness and low-income families. PHB invested in the building’s development in the South Waterfront (using TIF), partnering with REACH CDC, which now owns the building. The major limiting factor for city-developed housing is the lack of funds allocated for purchasing land and for development.

…- Affordable Housing Preservation: In 2008, PHB identified 11 privately owned low-income apartment buildings that were susceptible to being converted to market-rate rentals. Through a variety of federal, local, and private financing, PHB was able to preserve the affordability of the 11 buildings for the next 60 years. Whether this was a one-time campaign or will turn into a long term strategy for maintaining affordable housing stock has yet to be seen.

- Rental Assistance: Through a variety of government funding mechanisms, qualifying individuals can receive assistance with rents and mortgages.

- Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs): Portland has taken measures to encourage “granny-flats,” second units created on a lot with a house. While not explicitly an affordable housing tool, the addition of these types of housing units presumably offers renters a greater variety of unit sizes and therefore a greater variety of rents. Moreover, they also provide homeowners with rent income that can help them meet high housing expenses.

Other Cities’ Program and Policies

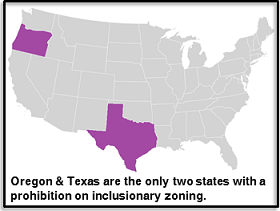

Inclusionary zoning: One tool that other cities and counties use to try to increase the supply of affordable housing is to require a certain percentage of units in new building projects to be affordable to people with low to moderate incomes. The practice of inclusionary zoning varies widely in how it is implemented, what percentage of affordable units are required, and even if the units have to be built on site or if they can be “transferred” elsewhere. Some affordable housing advocates see inclusionary zoning as a necessary tool to assure that housing is being built for a variety of income levels. Others argue that inclusionary zoning can actually reduce affordable housing options by encouraging older low-income buildings to be replaced by newer buildings with fewer units affordable to low income individuals. In either case, Portland is unable to employ inclusionary zoning because it is banned in the state of Oregon.

Inclusionary zoning: One tool that other cities and counties use to try to increase the supply of affordable housing is to require a certain percentage of units in new building projects to be affordable to people with low to moderate incomes. The practice of inclusionary zoning varies widely in how it is implemented, what percentage of affordable units are required, and even if the units have to be built on site or if they can be “transferred” elsewhere. Some affordable housing advocates see inclusionary zoning as a necessary tool to assure that housing is being built for a variety of income levels. Others argue that inclusionary zoning can actually reduce affordable housing options by encouraging older low-income buildings to be replaced by newer buildings with fewer units affordable to low income individuals. In either case, Portland is unable to employ inclusionary zoning because it is banned in the state of Oregon.

- Rent control: Some cities administer a rent regulation program that limits the amount a landlord may charge in rent and/or the amount rents can be increased. The most famous example of this is in New York City. While rent controls are clearly good for those whose apartments are under such restrictions, they also have been shown to reduce the supply of affordable housing available to new renters, and that drives up housing prices for everyone else. Portland is unable to employ rent control because it is a practice banned in the state of Oregon.

- Floor Area Ratio (FAR) Bonus: In some cities like Chicago, developers are allowed to build bigger buildings than the zoning code would normally allow if in return they dedicate a certain percentage of the building to affordable housing or if they contribute a certain amount of money to a city’s affordable housing fund. This is a tool that is designed to encourage lower cost housing in areas with high land costs. Dan Saltzman, the commissioner in charge of the Portland Housing Bureau, has expressed interest in developing a FAR bonus system in Portland.

- Transfer of Development Rights (TDR): One tool that cities use to protect farm lands and sensitive environmental areas is to allow development rights to be transferred from one site to another. Portland has this in very limited areas. For example, a property that would normally allow for the construction of an apartment project might be located in the Johnson Creek Basin. The city doesn’t want a development there so instead it allows the property owner to transfer the apartment units that otherwise could be built to another site in, say, Sellwood. This same system could be used to preserve affordable housing. A developer who would want to knock down an older apartment building and replace it with a new one could instead transfer the development rights elsewhere. This would keep the existing building in place, while allowing the developer to build something bigger in another location. This is a tool that exists in Seattle.

- Land banking/public lands: Even the small houses that Mayor Hales is envisioning need to be located on land (although I suppose they could be floating houses, too!). Land costs are a huge expense in affordable housing development so finding ways to use surplus or underutilized public properties could reduce some of the costs. Some cities, including Portland, use land that is already under government ownership. Other cities embark in programs of “land banking,” which involves acquiring vacant and underutilized properties from private owners for future development.

- Affordable Housing Funds: Cities have developed various mechanisms to dedicate revenue to affordable housing. In Highland Park, IL, for example, there is a tear down fee that is imposed on the demolition of single-family and multi-family homes that is put into a local housing trust fund. Other cities impose user impact fees such as Systems Development Charges to finance affordable housing development. New York City recently partnered with major financial institutions to create a $350 million affordable housing fund. Here in Portland, Commissioner Saltzman has even proposed setting aside 25% of the revenue from taxes on short-term rentals such as AirBnB for an affordable housing fund.

These are just a few of the tools that cities are using as they try to tackle the large, complex issue of affordable housing. I don’t claim to be an expert in this area so I’d welcome your thoughts and ideas. Shoot me an email – bob@seuplift.org – or give me a call at (503) 232-0010 ext. 314.

| Additional Reading |

Public Housing: Portland is not engaged in constructing the type of large-scale publicly owned housing projects that sprung up across the United States after World War, but instead there are projects such as

Public Housing: Portland is not engaged in constructing the type of large-scale publicly owned housing projects that sprung up across the United States after World War, but instead there are projects such as  Inclusionary zoning: One tool that other cities and counties use to try to increase the supply of affordable housing is to require a certain percentage of units in new building projects to be affordable to people with low to moderate incomes. The practice of inclusionary zoning varies widely in how it is implemented, what percentage of affordable units are required, and even if the units have to be built on site or if they can be “transferred” elsewhere. Some affordable housing advocates see inclusionary zoning as a necessary tool to assure that housing is being built for a variety of income levels. Others argue that inclusionary zoning can actually reduce affordable housing options by encouraging older low-income buildings to be replaced by newer buildings with fewer units affordable to low income individuals. In either case, Portland is unable to employ inclusionary zoning because it is banned in the state of Oregon.

Inclusionary zoning: One tool that other cities and counties use to try to increase the supply of affordable housing is to require a certain percentage of units in new building projects to be affordable to people with low to moderate incomes. The practice of inclusionary zoning varies widely in how it is implemented, what percentage of affordable units are required, and even if the units have to be built on site or if they can be “transferred” elsewhere. Some affordable housing advocates see inclusionary zoning as a necessary tool to assure that housing is being built for a variety of income levels. Others argue that inclusionary zoning can actually reduce affordable housing options by encouraging older low-income buildings to be replaced by newer buildings with fewer units affordable to low income individuals. In either case, Portland is unable to employ inclusionary zoning because it is banned in the state of Oregon.