Greenway Diversion: Recent History and a More Transparent Way Forward.

By: Terry Dublinski-Milton

North Tabor NA Transportation and Land Use Chair, SE Uplift Board Director at Large, BikeloudPDX Member.

The opinions and ideas in this article are the writer’s, and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Board of Directors of SE Uplift.

It has been over a year since our last newsletter installment about diversion on the Clinton Greenway (Bike Boulevard). Since then the city installed two diverters at 17th and 32nd to augment the existing one at Cesar Chavez, including a one way bike lane design for one block on SE 34th.

An official evaluation by the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) is in process, but according to a recent article by Bikeportland, the response by cyclists and local residents has been overwhelmingly positive. And although some may still feel that traffic diverters, like the ones on SE Clinton, are an unfair inconvenience to auto drivers, our regional government Metro is singing their praises. Even the Oregonian has editorialized that the SE Clinton Street improvements may need to stay.

In north-western Europe, these safety measures have proven to be such a powerful tool for calming traffic that they are standard practice. In Vancouver BC they doubled their bike mode share in four years partially because they build greenways with frequent, predictable, diversion.

In Portland, getting diverters installed is no quick or easy feat. For decades neighborhoods have lobbied the city for diversion to manage cut through traffic. Despite the long-time identified need and proven effectiveness, the amount of labor, volunteer energy, professional outreach and engineering required to make these small improvements has been vast. In the case of SE Clinton Street, it took extensive lobbying by BikeLoudPDX, and Safer Clinton, including a guerilla diverter installation by anonymous neighborhood volunteers.

This activism where concerned community members organize around the need for diverters on a specific greenway has merit as it creates community while neighbors work together to solve a common problem. It allows for local solutions to trickle up; thus when the proposal does come to the city there is overwhelming support.

However, this process for greenway safety improvements, or lack thereof, also pits neighbors of parallel streets against one another as neighbors worry about spillover traffic. Though this disagreement may build relationships, it also places neighborhood associations in the contentious position of mediating ad-hoc conversations about which streets should get what traffic control treatment. It also requires a substantial amount of city resources, in the form of staff time, to study the traffic volumes repeatedly over time to assess community identified trouble spots on greenways and determine if diverters are an appropriate solution.

Most troublesome though is the current ad-hoc process for traffic diversion on greenways results in inconsistent implementation and a lack of transparency or structure for how and when a greenway gets a diverter. This can further the divide between those communities with the access to power and resources to advocate, and those without access.

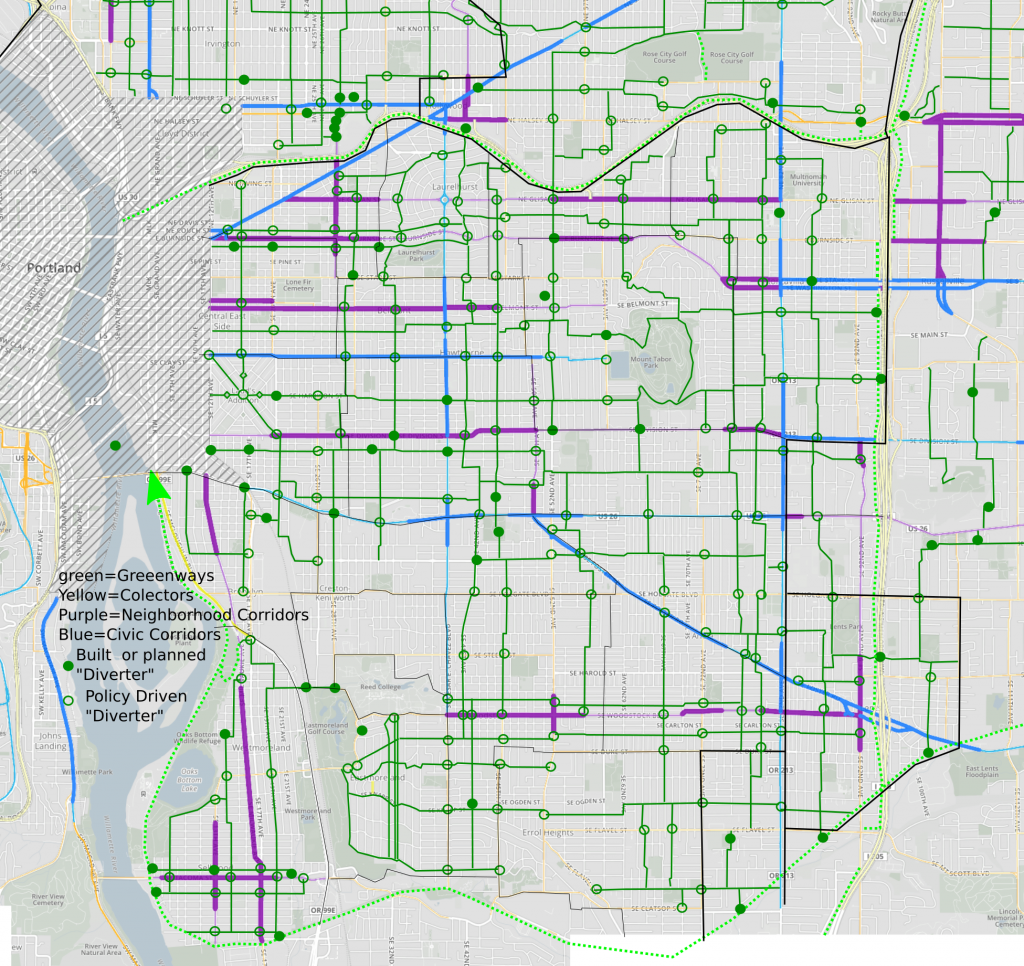

The Alternative Proposal: Diversion by Default

A “diversion by default” city policy for greenways crossing arterial streets would standardize greenway design and create transparency. Diversion at every main corridor would be norm, thus becoming a part of the urban form not much different than a crosswalk or traffic signal. The city could be required, by city code, to offer the community options for what kind of diversion would work for each coming project or to argue that one at that location is not possible and offer an alternative. Then it would be the community’s responsibility to provide feedback dependant on local needs. This type of predictable diversion benefits everyone: if you are a commuter auto driver and you see a greenway crossing you would know not to turn. Conversely, if you are a greenway active user you know that a fast vehicle won’t turn head on into you as the main corridor approaches. This would leave PBOT to monitor much less of our system over time for safety since preventative diversion would be engineered from the beginning of each project.

This diversion could be a “full pedestrian plaza,” a semi-diverter that only allows exits, a center median barrier, or maybe a treatment a few blocks into the neighborhood because of local circulation needs. We would need the widest amount of flexibility in design.

This policy may require us to improve neighboring streets as well to allow for Greenway construction, like around SE Woodstock or SE 82nd. Traffic light upgrades on main corridors to facilitate more auto throughput could also be needed. The comprehensive plan, climate action plan and 2030 bike plan call for the SE Portland area to at least triple our percentage of bicycle commuters over the next generation to help prevent gridlock, hence we need all the tools we can get.

As with any transportation change as we grow and become more dense, there will be winners and losers. Every time a new Greenway is built those living on that street benefit from slower and less traffic, but may have to change their own local commute patterns. Those on parallel streets might have to adjust to slightly higher traffic locally, but in the long-term this multi-modal design creates less congestion regionally as more residents will bike or walk.

Though there are city standards as to the allowed spill-over effects, the current policies are opaque and confusing for all involved. A straightforward greenway design standard requiring diversion at every main corridor, no matter the current traffic volumes, could organize this process in a transparent way without inevitably pitting neighbors against neighbors over every intersection as we would have time to plan, discuss and educate within a clear process.